Constant change is the essence of life

Constant change is the essence of life. It is often gradual, but sometimes so abrupt that it turns your world upside down. Then you have to find a new balance – but that usually takes some time. And that is just as well, argue Elke Geraerts and Jitske Kramer, from their expertise in neuropsychology and cultural anthropology. Because in the meantime there is a lot of beauty and opportunity for growth. In their Masterclass The Resilient Tribe ,they show how to make the most of this phase.

Crisis. Chaos. Transformation. They are big words for pretty mundane things. Most people’s lives are peppered with them: reinventing yourself after an illness or divorce, taking your career in a whole new direction with a swing, moving to another country, taking a trip that changes you forever. Often you can look back on it with a good feeling, but that doesn’t make the process easy: you know very well what you are leaving behind, but what you will find on the other side is still totally unclear.

NOT-KNOWING AS A BASIS

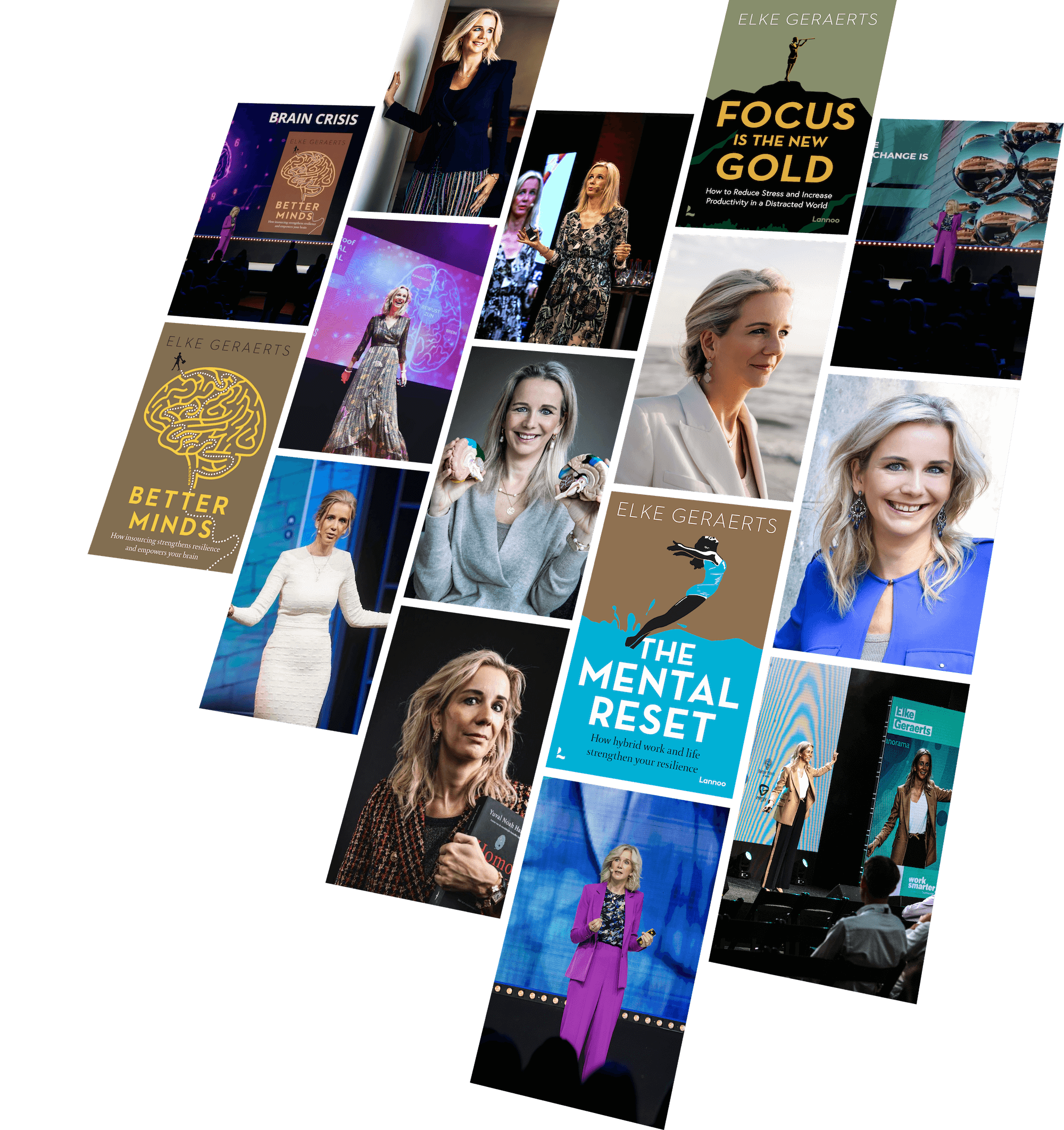

And that’s fine, says Elke Geraerts. She has a PhD in psychology and with her company Better Minds at Work she helps people and organisations activate their mental capital . “Often a crisis brings all kinds of opportunities to find new ways of living and working. You are almost forced to reinvent yourself. A crisis is not necessarily traumatic, in fact it can be very pleasant to move on to something new from there.” She often uses the image of the ‘learning pit’. “Many people think that change is always just an upward trajectory, but in fact they often first go through that pit full of self-doubt and uncertainty. They experience that as a crisis, but it is necessary to actually learn.” That more or less chaotic phase of not knowing is at the root of your personal growth.

Anthropologist Jitske Kramer, founder of Human Dimensions, traveller, speaker and writer, knows that this is no different for groups of people. What we think is normal – according to the norm – as a group is related to what we agree with each other. “People form cultures and cultures form people. What we define as normal together is not fixed. They are not laws of nature. And that means that what we consider right and wrong, normal and abnormal can be subject to change. At the same time, cultures benefit from continuity. We want to persist and then it is convenient to keep what we have. At least we know what to expect from it. We have set up our society accordingly with all kinds of social contracts and financial flows.”

Just changing is, of course, out of the question with such a construction – no matter how obvious it is that the old system is not sustainable. This creates a tension between the need for continuity and the need for change. “Take economic growth, the focal point of our society. Long seen as unstoppable, we must now recognise that it may cost more than it delivers. But around which new concept we will then organise ourselves is not yet clear. And besides, no one agrees.” As with personal change, such a cultural shift produces chaos, and a lack of control.

AN EXTRAORDINARILY WEIRD TIME

You can find all this very unsettling, but you can also come to terms with it, Jitske knows from her own experience. “I have gone through crises and transformations several times over the past 15 years,” she says. There was the year she was ill – a faltering thyroid gland – and suddenly couldn’t do what she wanted. A divorce followed a few years after that, another few years later a business that did not turn out to be what she hoped for. When her new venture was well and truly up and running, a pandemic followed. In the last few months, her new love is bringing great change to her life in yet another way. And always there is that same cycle: crisis-intermediate-transformation. “In anthropology, we call this interim time liminality, the meantime. It is characterised by chaos. You can resist that, but it doesn’t help you. Acceptance does. I have said to myself in all these big changes: I am now entering a very abnormal time, which might take a year. Certainly all seasons I’m going to have an extraordinarily weird time. And from there I’m going to slowly see what it’s going to be next. I didn’t think in those difficult moments either: I’m a bit crazy. No: I’m a bit liminal.”

Elke recognises it. After years in science, she realised she had drifted away from what she really wanted: direct contact with people, helping them in the workplace. She reinvented herself and became an entrepreneur. “A huge shift, from my still fairly safe cocoon to having to learn everything all over again. Suddenly having to learn how to read financial statements and how to do marketing and recruit clients.” It was not the first time she had to recreate herself and certainly not the last. In 2020, in the midst of the corona crisis, she divorced her husband. “That has a long impact. I have to transform as a person and as a mother, so that process is definitely not done yet. But even though I am still in the midst of it, I am already noticing some beautiful effects of that crisis. A more intense bond with my daughters, for example, just because I see them less often and therefore live more in the now with them.” Like Jitske, she finds solace in her profession: “Precisely because I know that I have had to rely on my resilience many times before. I rely on my brain set.” These thrive in the liminal phase.

So in the bubbling and bubbling of the Meantime, a lot is happening. How do you make the most of it?

THE JUNGLE OF YOUR BRAIN

First, let’s look at what stands in the way of a successful transformation. That, says Elke, is mainly the brain itself. Unfortunately: it often doesn’t feel like it at all. “Especially in times of crisis, of stress and anxiety, it is tempting for our brain to go down the established paths, to fall back on the habits of yesteryear. When you want to create new habits, you really have to carve a new path through your brain’s jungle. That takes time and effort. And people don’t like that. They then try to get around that learning pitfall, but that’s not a good idea, because then you avoid learning something new, you avoid innovation. In my field, I try to inspire people: how can you yourself become more aware of how your brain works, and how can you yourself have more impact on that?” Because the good news is that your brain can be controlled quite well. “In the master class, for example, we go into more detail on how to focus on your priorities. You can condition your brain to go straight to flow, to work undisturbed on what you really care about. A crucial skill to get through liminality well.”

Another danger is passivity. “That is also a very familiar reaction, the freezing out of the familiar queue of fight-flight-freeze. It is a state of hypo-arousal, the opposite of hyper-arousal, which is precisely a stressed, agitated feeling. People sit back, take no action and close their eyes to the chaos. They start waiting for things to improve on their own.” An understandable reaction, no doubt stemming from a sense of powerlessness, but you are not helping yourself or the world. It lacks the vision and guts needed for successful transformation. Elke: “Someone recently used the analogy of a building where people haphazardly build all kinds of rooms. Maybe a temporary solution, but eventually you drift further and further away from the ideal situation. People hardly dare to start with a clean slate.”

DARE TO STOP

While that is exactly what is recommended, Jitske also says. Break it down! “That is also part of transformation. Stopping. Saying goodbye. Letting go. That is complicated and sometimes not fun, but necessary to create space for the new. I find it an interesting phenomenon: in nature, everything has an end date. Birth and death follow each other in a logical cycle. But for organisations, we don’t know that concept at all: it always has to grow and keep going. Even if it hangs together from all kinds of artificial constructions, like Elke’s building. Whereas you could also say: we let it go, we give this company good death support with a terminal phase of about five years. Actually a liminal phase. And in that meantime we can start building something new, come up with a new system. Because there will be room for that.” On a personal level, it is no different.

Sounds good in theory, but then how do you deal with nostalgia for the old? Revel in it, is Jitske’s advice. And build a ritual around it. “Make sure you deeply accept what has been. Create a moment when you can long for it super nostalgically, a kind of mourning. Take a picture of it, eat a piece of apple pie, mark the moment. And then end with: well, so it’s not like that now.” Neuropsychology agrees, Elke knows: “It doesn’t help to push away negative feelings like that. It’s much better to let them in, to be able to process them successfully. At university, I did research on how people cope with a traumatic experience. With war veterans, but also victims of child abuse. And then you saw that reliving the trauma, rather than putting it away had a significant impact on their post-traumatic stress symptoms, in a positive sense. So I am absolutely in favour of daring to relive, taking time for that, noting to yourself that you have that hang-up.”

LEADERSHIP ACROSS TWO TRACKS

And you don’t have to do it alone. Jitske: “In anthropology, the chief and the shaman are familiar concepts. In a process of transition, you need both types of leadership. The chief to keep daily affairs in order in all the chaos, and the shaman who can create something that is not yet there. This applies to a society, but equally to individuals. For example, when I was so sick, I needed someone to say to me: now you go to sleep, and then you get up so late and then you get dressed. A chief who provided structure, because I couldn’t do that myself at that time. At the same time, I also felt the need to talk to someone: if I don’t get my old life back, what is there? That’s liminal leadership then, you start talking to people who understand the in-between: coaches, therapists, artists, spiritual leaders. I had a therapist myself, an Englishman, who said, ‘You’re at the place where your soul is being built. Now you go build it.’ And then I said, ‘But how?’ And then he replied: ‘Well, usually it helps when just lay yourself on the couch and put a blanket over your head.‘ Just go and be with the suffering, listen to your body and what it needs. Allow the despair. That really helped too. And then combined with that other person, saying, ‘OK, but it’s good to eat something now. And take steps to take action.'”

Both stress the importance of positivity and confidence in the liminal phase. “Words create worlds,” says Elke. This applies not only to how you talk to yourself, but also to how we talk to each otherin society . Negativity and cynicism are good for ratings and newspaper circulation, but in the meantime you perpetuate the idea that everything is only bad. That in turn leads to that passivity and so we talk ourselves into an endless liminal phase, instead of working on real transformation.” Not that everything has to be rainbows and flowers all the time, Jitske warns. “The liminal phase is an emotional phase. It is about doubt, sadness, parting, hope, expectation. Organisations often dismiss this as floaty stuff that gets in the way of productivity and efficiency. But precisely in that softening is also the opportunity for connection and renewal. I think that in liminality we need to have the guts, create the cultural normality, that it’s okay to engage in conversation on that softer piece.” That is precisely what helps in processing, in building trust, in living through a transition. In sharing emotions and connecting with each other, is the path to transformation.

Tekst: Peper Hofstede

Elke’s TEDx talk

Constant change is the essence of life.

When AI meets AI

Elke's newsWhat happens when you bring together an entrepreneur with a passion for people with an entrepreneur bitten by technology and innovation? That is what we discover at the conference Ten years of Better Minds at Work where Elke Geraerts and Peter Hinssen...

Podcast BNR: Positive Thinking

Elke's newsIn times of crisis, it is often tempting to bury your head in the sand. But precisely then, a proactive attitude is crucial. Elke Geraerts discusses how to achieve this in BNR’s Big Five alongside Diana Matroos. The other guests in BNR’s Big Five on...

NEWSLETTER

Sign up for Elke’s newsletter